Special Editorial — Gil Gerard, the Last Great Sci-Fi Hero

Special Editorial — Gil Gerard, the Last Great Sci-Fi Hero

Jeffrey Morris

Founder & COO, FutureDude Entertainment

Writer/Director/Designer

When news broke that Gil Gerard had passed away this week at the age of 82, I was saddened, but I was also very surprised by the sheer volume of response online. Dozens and dozens of friends and acquaintances shared stories, images, and memories. It was a powerful reminder of just how deeply he resonated with so many of us who were growing up at the time.

I was in seventh grade when Buck Rogers in the 25th Century was released as a feature film. My father was especially excited—he had grown up watching the Buck Rogers serials in theaters back in the 1930s, and this felt like a bridge between his childhood and mine. We went to see it as a family, and I remember being completely taken by it. We all loved it.

I really got into the film, especially the idea of Captain William “Buck” Rogers—a contemporary astronaut—waking up 500 years in the future and experiencing an advanced civilization on Earth. It was something I desperately wished I could do. In addition to having a raging crush on Erin Gray’s Col. Wilma Deering, I was equally obsessed with the film’s central spacecraft—the agile Thunderfighter. It felt fast, purposeful, and elegant in a way that spoke directly to my imagination at that age. The design is my all-time favorite space fighter and still holds a special place for me. In fact, one sits on my shelf in my office to this day.

When the television series followed, I wanted to love it just as much as the movie. I really did. But, to be honest, something felt off. The production values were lower than I had hoped for, and the show’s tone drifted into camp. The second season only amplified those issues, and it became harder to ignore the things that weren’t working. And yet—I kept watching.

Looking back, I understand why. I wasn’t watching for the show. I was watching for Gil Gerard and his portrayal of Buck Rogers. There was something magnetic about him. His presence carried the material far beyond the limitations of the scripts or the sets. He brought confidence without arrogance, strength without cruelty, humor without cynicism.

Gerard’s Buck Rogers felt like a real hero—capable, assured, but grounded. There was warmth and humility in the performance. A sense that heroism wasn’t about domination, but about character and a smile. He represented a version of masculinity and leadership that felt aspirational without being aggressive.

You didn’t just want to watch him—you wanted to be like him. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to believe something else: Gil Gerard may have played the last great, classical sci-fi hero.

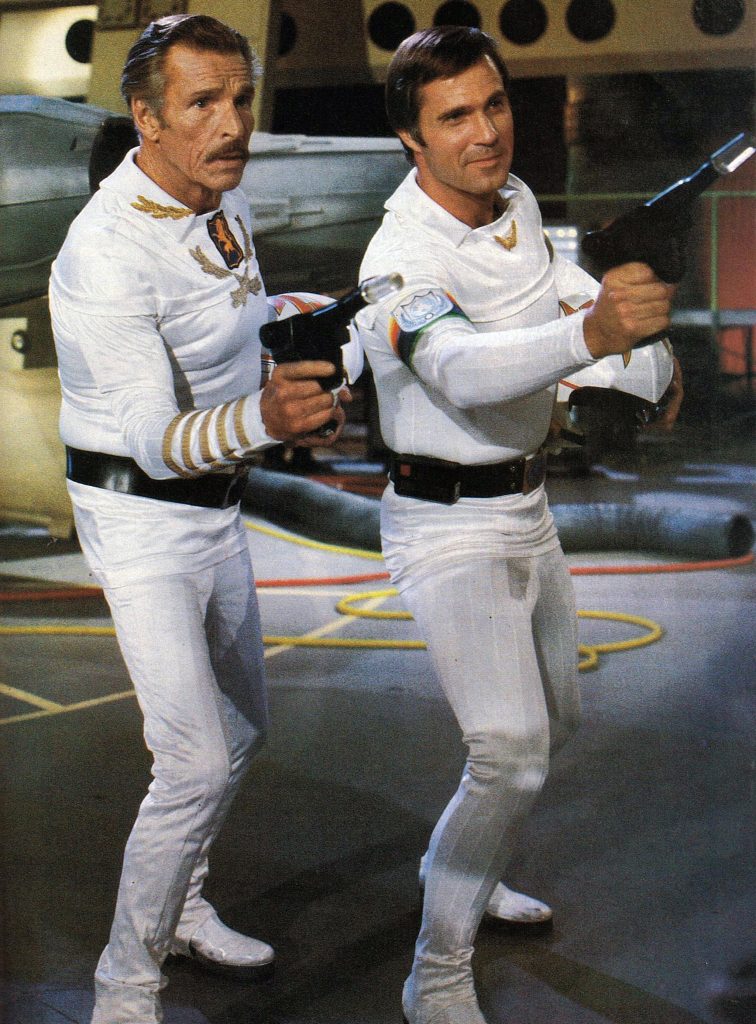

When I think about the lineage—Captain Kirk (Star Trek), Alan Carter (Space: 1999), Captain Apollo (Battlestar Galactica), and finally Buck Rogers—there’s a clear through-line. These characters weren’t anti-heroes or damaged figures pushing forward despite themselves. They were competent, ethical, curious, and fundamentally optimistic. They believed the future was worth engaging with, not merely surviving. In an era where our stories increasingly reflect exhaustion, distrust, and moral paralysis, the absence of heroes like that feels less like evolution and more like something quietly lost.

After Buck Rogers, that archetype largely disappears. Science fiction didn’t stop producing protagonists—but it stopped producing heroes in the classical sense. The genre turned inward. It became darker, more ironic, more suspicious of its own ideals. Characters fractured into ensembles defined by snark, or were deliberately undercut, or written to resist admiration altogether. Even when stories were intelligent and well-crafted, their central figures were often shaped by trauma, ambiguity, or moral fatigue.

I love characters like Firefly’s Malcolm Reynolds and James Holden from The Expanse. They’re strong, compelling, and often noble. But their worlds are steeped in violence and cynicism, and their heroism exists under constant pressure. It’s a darker lens—one that can feel oppressive in its insistence that optimism must always be earned through suffering.

Gil Gerard’s Buck Rogers was different. He was an embodiment of hope. He stood at the boundary between two eras. He was the last leading man in science fiction who could carry optimism without apology. Buck wasn’t naive, but he wasn’t cynical either. He trusted reason. He trusted people. He trusted that progress was possible if we chose it.

That’s why the character of Buck Rogers matters even more now than he did then. He represents a fork in the road—a moment before science fiction stopped believing in its own promise. Before it became embarrassed by hope. Before optimism was treated as naive rather than courageous.

Judging by the outpouring of affection I’ve seen over the past few days, I know I’m far from alone in feeling that Buck Rogers really mattered. Gil Gerard mattered. In a very real way, he helped pass something forward—from my father’s generation, to mine, and to anyone still willing to believe that the future is something we can choose to build.

For many of us, he defined what a hero could be.